Posted on: 10th March 2025

Note: This page provides a shortened summary of the extensive case study, which includes the research, the simulation and Matrix scoring results, as well as recommendations. For the whole 30 page document, simply click here and download as a .pdf file.

Introduction

The energy transition in Sweden is characterized by a shift towards renewable energy sources and increased energy efficiency. A significant aspect of this transition is the emergence of energy prosumers — individuals or entities that both produce and consume energy. Prosumers play a crucial role in this transition by increasing self-consumption and energy efficiency, participating in community energy initiatives, and contributing to a decentralized and democratic energy model.

The Jakobsgårdarna area is located in Borlänge, a city in Dalarna County, central Sweden. In this region, one critical aspect of the regional approach to sustainable development is the formulation of a comprehensive energy and climate strategy. This strategy outlines a long-term vision for the year 2050, envisioning Dalarna as a place where living in an “energy intelligent and climate smart” manner is not just encouraged but has become second nature to its residents.

To attain Sweden’s goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2045, various initiatives, programs, and legislations have been introduced by both the government and society. As of October 2021, a total of 23 cities in Sweden, including Borlänge, have entered into Climate City Contract 2030 (CCC). It is a collective effort to achieve the climate transition that we need to implement in a short time to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees. CCC is an agreement between municipalities, government agencies and Viable Cities where all parties undertake to make a concrete contribution to increasing the pace of climate change (Viable Cities, 2024).

Jakobsgårdarna area presents an ideal candidate for a baseline PED case study. The community’s alignment with Dalarna’s energy and climate strategy, as well as its commitment to the Generational Goal, makes it a compelling example of how sustainable living principles can be put into practice. Studying Jakobsgårdarna’s journey towards energy efficiency and climate resilience can provide valuable insights and serve as an inspiration for other regions and communities striving to achieve similar sustainability goals. It showcases development plan for this district. This initiative is driven by the presence of a substantial land reserve, which holds significant potential for the creation of housing units and the integration of various social and economic activities.

2. Methodology of Research

This study employs a mixed-method approach, combining desk-based research, participatory engagement, interviews with stakeholders, and energy performance simulations to generate a comprehensive understanding of the energy community and its potential for improvement.

An energy performance simulation was carried out to evaluate the energy efficiency of buildings within the community. The simulation assessed the current energy consumption and identified potential improvements.

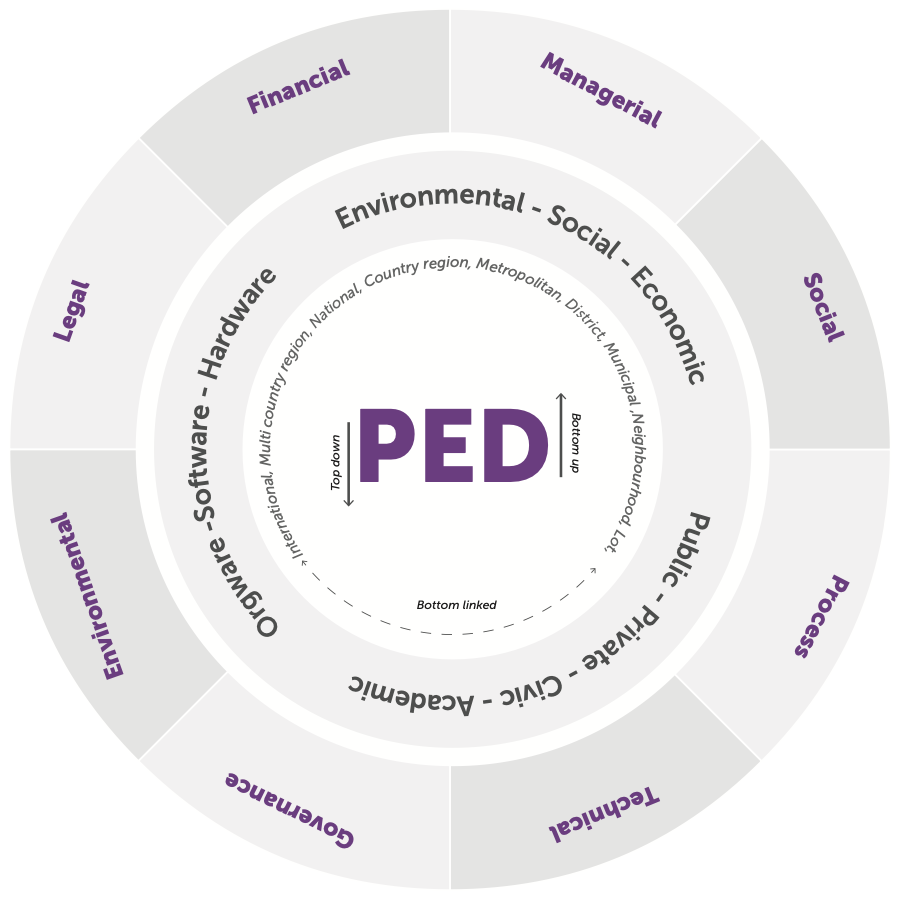

To synthesize the qualitative and quantitative data, a Positive Energy District (PED) matrix was developed. The matrix allowed for the systematic evaluation of the current situation and areas for improvement across multiple dimensions, such as energy performance, governance, and community engagement. This structured analysis facilitated the identification of potential synergies and challenges, offering insights into pathways for optimization.

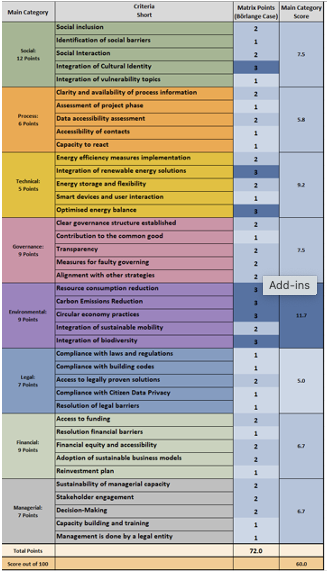

An evaluation methodology is designed to assess the cases across eight key aspects based on PED matrix: Governance, Technical, Legal, Financial, Environmental, Social, Process, and Managerial. Each aspect is evaluated through a set of criteria that focus on critical elements required for PED success. A structured scoring system is applied to each criterion using a 0 to 3-point scale, where higher scores indicate stronger alignment with PED objectives. Ultimately, an overall score is generated to compare different cases across various contexts, fostering a learning environment between them.

Assessment of the case based on the PED Matrix criteria

To effectively manage and implement Positive Energy Districts (PEDs), various aspects must be taken into account. The PED-ACT project developed a comprehensive matrix to assess the potential for PED development in Borlänge case, addressing key aspects such as social, process, technical, governance, environmental, legal, financial, managerial. Below is a matrix highlighting these dimensions, and further explained in the following text.

Overview of key scoring aspects

Social Aspects

Stakeholder engagement is moderate. Most large local companies have signed agreements with the municipality, and some small companies have joined as well. Many individuals are interested in the process and are well-informed through annual workshops and conferences, particularly for the CCC initiative. The identification of social barriers is limited. Some barriers were recognized in another research project, but the municipality has not taken significant action. The CCC initiative tends to be a top-down policy, and many social barriers are overlooked.

Social interaction within the energy transition project is moderate. While there is an annual event for the CCC, no specific activities are organized for PED or energy communities. Conversations mainly occur among companies rather than individuals. The integration of cultural identity is strong. The community already has a strong connection to sustainability. The integration of vulnerability topics is limited.

The CCC approach is top-down, and vulnerability issues are not prioritized or adequately addressed.

The Process

The clarity and accessibility of information is moderate. A website dedicated to the CCC of Borlänge ( https://klimatneutralaborlange2030.se/) provides some details, but accessing more in-depth and detailed information, particularly about the current phase, is not straightforward. The phases of the project are partially identified. While there are several projects branded for CCC, obtaining useful information about the specific stages of the process and current status is challenging. The CCC target is clear, and a roadmap exists, but detailed information is not easily accessible.

Data accessibility is limited. Some data is available, but understanding and accessing it requires contacting the right person. Comprehensive, easily accessible data for stakeholders is lacking.

Technical Aspects

Energy efficiency implementation is poor. While many new buildings meet energy efficiency standards, numerous existing buildings require in-depth renovation to improve energy performance. Renewable energy solutions are integrated. Solar energy is popular, and other renewable sources, such as biomass and waste heat, are common in the city.

Storage options are limited. Although a large storage system is planned for implementation soon, individual storage options for energy flexibility remain limited. The integration of smart devices is poor. Smart devices are not widely adopted, and the district heating company usually controls the system centrally. While electric vehicle smart charging is becoming popular, other forms of smart energy management are not common.

The energy system provides adequate coverage of local needs. The majority of energy comes from sources, primarily waste combustion, while heat is mainly supplied by heat pumps. However, there are still opportunities to optimize energy production and consumption .

Governance Aspects

The governance structure is moderately developed, aligning with the legal framework for energy communities. While responsibilities and decision-making mechanisms are defined, the system is not yet optimized for full energy autonomy. It effectively informs the management team, but there is room for improvement in operational efficiency.

Co-creation opportunities are limited in this early stage of the energy establishment. Stakeholder involvement is minimal, with no clear pathways for collaborative decision-making. The governance framework does not yet mandate or prioritize active participation.

Environmental Aspects

The pilot demonstrates a high reduction in energy and resource consumption through the adoption of efficient systems and sustainable practices.

Circular economy principles are strongly embedded within the pilot, with innovative programs focused on waste reduction and resource recovery. The pilot effectively utilizes measures that promote reuse, recycling, and waste management, contributing to overall sustainability goals. The Integration of sustainable mobility is moderate. There are sustainable mobility solutions but coverage and accessibility are still limited. Although infrastructure for low-emission transportation options is in place, further efforts are needed to expand its reach.

Biodiversity is extensively integrated into the pilot’s development, with sustainable measures in place to ensure a positive environmental impact. The project emphasizes maintaining and enhancing habitats, contributing to the long-term preservation of biodiversity in the area.

Legal Aspects

The case is considered to have poor alignment with compliance to laws and regulations because there is minimal regulatory alignment with climate goals, which are not clearly defined for citizens or energy communities. The legal framework for energy communities, such as trading and storing energy, is somewhat feasible but heavily dependent on decisions made by energy providers, which can change quickly. Additionally, the legal framework for energy communities is still in development and has undergone significant changes during its few years of implementation.

The energy community faces significant barriers in complying with building codes and land-use regulations, particularly due to constraints like heritage protection laws and local rules governing prosumers. These limitations hinder the adoption of innovative concepts and technologies, impeding progress toward more sustainable energy practices.

Financial Aspects

The pilot has moderate funding possibilities, with some eligibility for both the community and its members. However, access to financial resources is limited, especially for acquiring specific energy solutions such as thermal or water energy systems.

The project faces a low degree of financial resolution, as members depend heavily on fluctuating incentives, particularly for photovoltaic (PV) solutions. The pilot’s financial strategy relies too much on external factors. These incentives are subject to change, which introduces uncertainty and risks for the financial sustainability of the project.

The project demonstrates a moderate commitment to financial equity, offering some support to underrepresented or low-income groups. However, accessibility is limited, with only partial subsidies or support programs in place, meaning that the most vulnerable community members may not fully benefit from the project’s opportunities.

The energy community employs a moderately sustainable business model, focusing on energy production and consumption by its members. While the business plan is viable in the mid-term, risks regarding return on investment (ROI) lie primarily with the energy solution owners. The model ensures some level of financial stability but lacks comprehensive sustainability across all pillars.

Managerial Aspects

The energy community has a moderate level of managerial capacity, as it is managed by a board. However, there is no long-term sustainability plan in place for management, which could impact the operational efficiency and continuity of the project in the future.

Stakeholder engagement is limited, with only a few individuals signing agreements related to the community energy initiatives. While there are annual workshops and conferences focused on sustainability, many local residents have a relatively good awareness of sustainability practices in their daily lives, but overall awareness about the energy project remains lower.

The decision-making process within the energy community is moderately clear, with established values guiding the project. However, not all members fully understand or have an overview of the process, and there is a lack of clarity in integrating these decision-making practices into the daily operations, particularly for transitioning to a Positive Energy District (PED).

Capacity building is still in its early stages, with limited training and development opportunities for both the management team and community stakeholders. The energy community is at the development phase, and there are minimal plans to expand capacity-building efforts or enhance skills within the community at this stage.

The energy community operates with a poorly developed legal entity, which currently functions on a basic level, managing energy-related activities with limited member engagement. While the entity is functional, there is potential to expand its role in managing energy projects in the future as activities grow and become more complex.

Jakobsgården’s integration of renewable energy, energy-efficient technologies, and stakeholder engagement showcases Sweden’s commitment to local carbon reduction. These lessons extend beyond Borlänge, providing scalable insights for sustainable communities—a testament to Sweden’s proactive stance in addressing climate change and promoting innovation. These efforts resonate with the PED-ACT project’s mission to support communities in their journey toward energy sustainability and positive environmental impact.

This study was performed within the research project PED-ACT. The primary goal of the project is to rectify the longstanding issue in the design iteration of PEDs, where conventional top-down approaches have been predominant. These approaches, while occasionally effective, have consistently struggled to establish genuine stakeholder ownership, and superficial stakeholder engagement has proven insufficient for achieving authentic co-creation.